By Kirsten Han for WE, THE PEOPLE: https://www.wethecitizens.net/yncuspmergerclosure/

This piece morphed and evolved as I wrote it over the past few days. I didn’t want to rehash things that were already being reported by the local media, so I was looking for a way We, The Citizens could add value to what’s out there. I ended up putting this together based on existing reporting, conversations with faculty and students, and my personal observations/interactions with Yale-NUS students over the years. I hope this will be useful in summing up what’s happened so far, what some of the public discussions have been, and why this is more than just about administrative shifts in academic institutions.

I usually only email special issues to Milo Peng Funders before making the piece available on the website, but today I'm sending this one out to everyone.

(One housekeeping note: I sometimes label a special issue a “WTC Long Read” but realised that I’ve never defined what this actually means! From now on, “WTC Long Read” will refer to special issues that are over 3,000 words long.)

Last Friday morning, the National University of Singapore (NUS) announced that Yale-NUS College and the University Scholars Programme (USP) would be merged to form a “New College”. For all intents and purposes, though, it looks more like the closure of Yale-NUS; the college will cease to exist after the current cohort of freshmen graduate in 2025. Yale-NUS will no longer accept new students after this academic year, and the New College will admit students from the 2022/23 academic year on.

As fast and unexpected as a lightning strike

This announcement came as a shock to almost everyone, most particularly the faculty and students of Yale-NUS College and USP. While some say they’d guessed that this liberal arts tie-up between Yale University and NUS would one day come to an end, there’d been no indication that such an announcement was going to be made now. Students told Channel News Asia that they’d only been informed on Thursday that Friday morning classes were cancelled. The next morning, they were given a link to attend a virtual town hall. But it wasn’t actually a town hall, which would have emphasised participation and listening to constituents’ concerns. It was in a webinar format, and no questions were taken. There was then a breakout session, but it wasn’t much of a dialogue either. Questions could only be sent in, upon which they were read out and answered. Obviously, there wasn’t enough time to address everyone’s queries.

For Yale-NUS students, it feels as if the rug has been pulled out from under their feet. The new academic year opened earlier this month, which means that tuition fees for the semester have already been paid. This isn’t cheap: according to the college’s website, tuition fees (not including residential college and other miscellaneous fees) for the current academic year stand at over $20,000 for Singaporeans, over $31,000 (without tuition grants) for Permanent Residents, and over $45,000 for international students. Trying to transfer to a new university now would likely be challenging. A first-year student told The Straits Times that they’d turned down offers from other reputable institutions in favour of a Yale-NUS education, only to find out now that their college will be defunct by the time they graduate.

As things transition, how different will people’s jobs end up looking from what they’d originally signed up for? The fact that no one knows the answer just adds to the shock, anxiety, sadness, and anger.

Faculty, from new hires to old-timers, have been blindsided. Just weeks ago they’d have been prepping for the semester’s opening, without a clue of what was to come. Money, time, and energy have been spent reviewing curriculum. Now, lecturers and academics are wondering what will happen to their courses and their jobs. NUS has stated that no one will be made redundant and that all contracts will be honoured, but there isn’t much detail beyond that so far.

“[As] the number of students declines, there will likely be opportunities to teach the New College students or to be engaged with other NUS departments,” it reads on the Frequently Asked Questions made about the New College. Yet no one knows what that will look like; NUS doesn’t offer the same sort of interdisciplinary programme that Yale-NUS does, and it’s not clear how things at the New College will turn out. As things transition, how different will people’s jobs end up looking from what they’d originally signed up for? The fact that no one knows the answer just adds to the shock, anxiety, sadness, and anger.

A decision made, just like that?

Things appear to have moved very quickly. Back in January this year, the college was still welcoming a new Dean of Faculty and quoting proud Yale-NUS and Yale administrators who celebrated the partnership and its expected longevity. “NUS shares a deep relationship with Yale, and this appointment illustrates Yale’s strong ties to the College and its commitment to the success of Yale-NUS,” Tan Eng Chye, NUS’ President, was quoted as saying. Pericles Lewis, Vice President for Global Strategy and Vice Provost for Academic Initiatives at Yale University, even talked about Yale-NUS entering “its second decade”.

It seems that Tan changed his mind over the course of the next six months. According to reporting by Yale-NUS College’s student paper The Octant, Tan first raised the idea of dissolving Yale-NUS with the Ministry of Education in June this year, before speaking to Yale University’s President Peter Salovey in July. A statement from Salovey on Yale’s website states that “we would have liked nothing better than to continue its development”, indicating that the desire to end this relationship was solely on NUS’ part. The agreement between the two universities allows either party to withdraw unilaterally, with one years’ notice, in 2025.

Even Tan Tai Yong, the President of Yale-NUS, wasn’t consulted; he told student reporters that the decision had been presented to him as a done deal, and that he'd been "gobsmacked and flabbergasted". It was endorsed by the Yale-NUS Governing Board on 23 August. It’s not like they had a choice; according to Tan Tai Yong, the board has “procedural obligations” to endorse the decision.

When I asked Kristopher Olds, a professor in the Department of Geography at University of Wisconsin-Madison who researches the globalisation of higher education and research, for his thoughts on this situation, he sent me this:

Thank you Prof Kristopher Olds for sharing this with me!

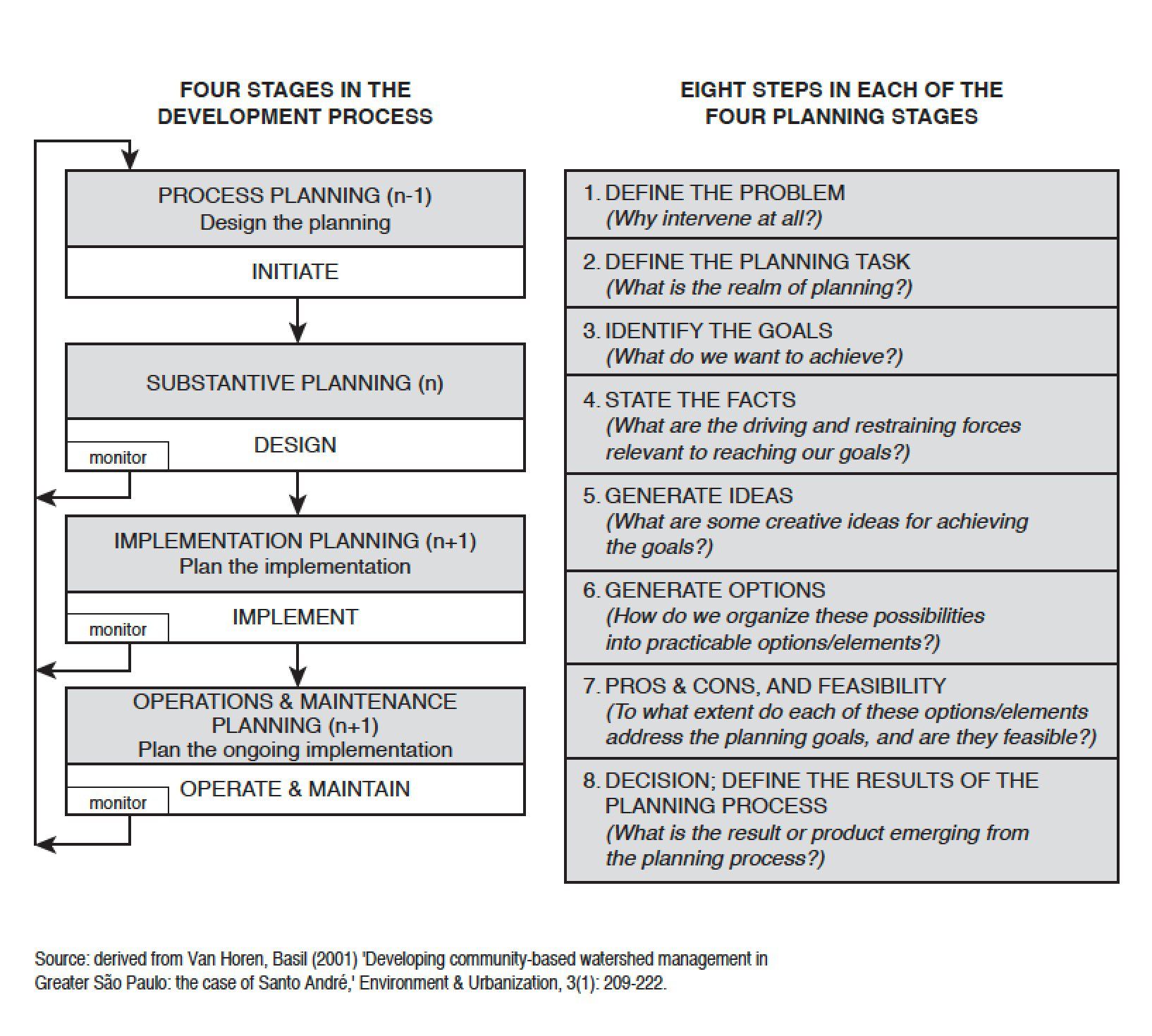

"What’s worth thinking about is that this is the outcome of a planning process. There are eight steps in a typical planning process (see the attached visualization), and NUS leadership appears to have internalized them all," he said.

"They planned the planning process, and they did the substantive planning. They moved very quickly, in a top down manner, but the jury is out as this type of accelerated planning reduces buy-in, potentially generates blowback from relevant stakeholders, and fails to factor in diverse perspectives on the goals and processes."

It seemed odd that a development of such magnitude could happen at such speed. I reached out to multiple academics from various tertiary institutions, to ask if such a sudden announcement of closure is common. So far, their answers suggest that this is not normal, especially if we consider Yale-NUS’ situation. There might have been instances of centres or specific programmes within universities being suddenly shut down—and even these developments can generate huge amounts of controversy, or allegations of censorship or interference—but announcing the closure of an entire college, with zero consultation (not even with its own president?!), zero hints, and zero warning, is highly irregular.

Some colleges in the United States have shut down (and quite quickly, too) in recent times, collapsed under the weight of financial difficulties exacerbated by the pandemic. Others have opted to close amid dwindling enrolment. There is increasing talk of university mergers, some of which were opposed for months. In some of these cases, students have been left even more in the lurch than those at Yale-NUS. But Yale-NUS is not in a state comparable to those struggling colleges. It’s been largely funded by the Singapore government, and is a highly sought-after college with a low admissions rate of only 6%. (In 2017, it was reportedly even harder to get into Yale-NUS than to go to actual Yale.) So it doesn't seem to be about the money, and certainly isn't a problem of low demand.

Why is this even happening?

NUS has framed this development as “a step that furthers the mission of interdisciplinary liberal arts education.” However, many reactions to the news—whether in favour or not—relate to the viability of such a liberal arts college in Singapore: some say that the autonomy and freedom required for a true liberal arts education was never going to endure in an authoritarian state, while others say that the “American values” of such an institution was “incompatible” with Singapore in the first place.

This is not a new topic of discussion. It was already a matter of controversy when the tie-up was first announced in 2011. The decision was slammed by Yale Daily News back then, and other Yale faculty expressed reservations about such a collaboration, citing concerns about academic freedom.

Some say that the autonomy and freedom required for a true liberal arts education was never going to endure in an authoritarian state, while others say that the “American values” of such an institution was “incompatible” with Singapore in the first place.

In 2019, the issue of academic freedom again came to the fore following the cancellation, at short notice, of a workshop entitled “Dialogue and Dissent”, curated by playwright Alfian Sa’at. (Full disclosure: I was originally scheduled to facilitate a democracy classroom session as part of the workshop.) The college administration claimed that it had been cancelled due to a lack of academic rigour instead of political pressure, and an investigation by Yale, headed by Pericles Lewis, who was also the first President of Yale-NUS, found no evidence of government coercion. The findings, however, were critiqued by a senior Singaporean lawyer, whose analysis found that “the evidence raises, at a minimum, justifiable doubts whether there were sufficiently strong academic or legal reasons to cancel the program” and “that the likely dominant factor behind the cancellation was the ‘political nature of the program’”. The episode led to the Yale FAS Senate recommending that Yale “establish clear criteria and procedures to determine if and how Yale should publicly respond to any such events in the future.”

Lewis has said that academic freedom was not a factor in the decision to close Yale-NUS College either. “We’ve been very satisfied with the ability of Yale-NUS students and faculty to exercise their academic freedom and have a really great experience there. That has not been a problem from our point of view,” Yale Daily News reported him saying. I reached out to multiple Yale-NUS College faculty for this story. None were willing to go on the record, the uncertainty of the situation heightening concern about repercussions.

Regardless of whether it was or wasn’t a factor in Yale-NUS’ current woes, there are enduring concerns about academic freedom in Singapore. A survey conducted by Academia.sg, which received responses from 198 academics from five universities, including NUS, found that:

While the majority of academics sense no restrictions on their own freedom, a significant minority do. Faculty who say they work on “politically sensitive” topics are 1.5 to 3.5 times more likely to feel constrained in their ability to research or engage the public compared with those whose work is not “politically sensitive”.

Even amongst those who do not feel personally constrained in their research, 64% acknowledge that scholars are subject to interference or incentivised to self-censor at least occasionally. For those who do feel personally constrained, 93% report the existence of interference and self-censorship.

A loss for organising and activism

The announced changes aren’t just a matter of shifting programmes, modules, and faculty around. Curriculum is of course important, but there are much wider repercussions. Yale-NUS College has provided a relatively free space for students to engage in organising and activism on campus. Groups driven by, or involving, Yale-NUS students have worked on issues ranging from the climate crisis to LGBTQ equality to political education and engagement. In 2018, a sit-in was even held within the college to express students’ unhappiness with a lack of accountability and transparency from the administration. Members of civil society have also been offered opportunities to speak and interact with students; I myself have participated in panel discussions, workshops, and democracy classrooms, covering a range of subjects from social movements to “fake news” to press freedom, organised or co-organised by Yale-NUS students and/or faculty.

The impact of this activism is felt beyond the college. Making the most of the generally permissive and supportive environment of their college, Yale-NUS students have invited their peers from other colleges and universities to join in on activities and initiatives. Student groups also collaborate and link up with NGOs and other civil society organisations, standing in solidarity on issues of national concern. Some who got their political awakening on campus continue with their activism and civil society work even after they graduate, bringing their energy and enthusiasm into existing networks. There’d been more talk of tightening control and curtailment in recent years, yet it still felt like there was possibility, something that can’t be taken for granted in Singapore.

In a country where progressive activism is suppressed and there are so few spaces for organising, every bit—no matter how imperfect or how limited—is precious.

This doesn’t mean that student or youth activism is a uniquely Yale-NUS phenomenon, nor should it suggest that Yale-NUS is some magic shot in the arm for progressive social movements in Singapore. But so much of the time, young Singaporeans interested in political issues are lectured, talked down to, policed, and told that they are too ignorant, too young, too [insert condescending excuse] to participate. In a country where progressive activism is suppressed and there are so few spaces for organising, every bit—no matter how imperfect or how limited—is precious.

For many of us in civil society, the unhappiness over this announcement isn’t about Ivy League brand names or prestige, but about the loss of a space—again without transparency or accountability or care—for young Singaporeans to explore their political views and engage in action beyond the classroom. There’s no guarantee that the proposed New College will offer such opportunities; while we hope that this culture and environment will persist and be offered to more students in the future, experience has taught us to be wary and apprehensive.

Historical comparisons have been made. In August 1980, Nanyang University, a private Chinese-medium university better known as Nantah (南大), held its last convocation ceremony. It was then merged with the University of Singapore to form the National University of Singapore. But, as with Yale-NUS students today, Nantah graduates don’t remember this change as a merger. They remember it as the closure of a beloved institution that was important to them.

Nantah’s end was officially explained as a logical move informed by lower enrolment as Singapore moved towards English-language education across the board, but it also had the effect of shutting down a large chunk of student organising. Even today, it’s not hard to find older Chinese Singaporeans—especially former Nantah students, or those close to them—who believe that that was the true reason for the closure of the people’s university. There are still people who feel the pain and loss of a school that’s been defunct for over 40 years.

Nantah isn’t the only parallel here. Lim Jingzhou, a community worker and final-year student at Yale-NUS College, put it best in his Facebook post:

My initial reaction to hearing the announcements first hand was feeling numb: this is Singapore, all over again. The erasure of identity, destruction of community, the unilateral decision-making without consultation, the processes which lack care and support for those who suffer the most and gain the least from such decisions, a blind pursuit for more and for scale, the loss of space, culture and spirit. Numb, because it keeps happening again. More than 5 years now working across three sites and communities being forced to relocate and resettle. The regular news cycle of something (buildings) being demolished, something (green spaces) being cleared, something (thriving human spaces) being forced to alter or subject to being taken away. Scary, because nothing seems to be able to stop it from happening again. Because we don’t quite ask if there is a pattern here. Because across different interests and communities, there isn’t enough conversations about how these are all fundamentally the same things happening in different ways.

So... what now?

There’s been an outpouring of emotions, reactions, and hot-takes on social media. While the Yale-NUS community mourns their loss and wax lyrical about the benefits they’ve reaped, others point to a “Yale-NUS exceptionalism”, criticising the college’s elitism. Some have taken umbrage with initial expressions of grief and praise for Yale-NUS, seeing it as a slight on the curriculum, rigour, and academic freedom of other departments and faculty outside of Yale-NUS. Others put this move in the wider context of the neoliberal commodification of higher education.

It’s not clear how much room people have to manoeuvre or work for the reversal of NUS’ decision; Tan Tai Yong certainly seems pretty pessimistic. Still, the students are putting up a fight; students from various faculties of NUS have launched #NoMoreTopDown, a petition criticising the university’s top-down modus operandi and rejecting not just the merger of Yale-NUS and USP, but also the announcement to combine the Faculty of Engineering and the School of Design and Environment to form the College of Design and Engineering. At the time of writing, the petition has garnered over 6,800 signatures. (Another petition, focused on Yale-NUS, has over 600 signatures so far.)

From my conversations and observations, it’s unlikely that Yale-NUS faculty feel empowered or safe enough to speak too publicly and critically. There’s hope for solidarity from academics at Yale University in the US, who have more latitude to demand transparency and accountability from their own university administration about how this decision came about, but it isn’t clear whether that solidarity will be forthcoming. To some Yale academics, Yale-NUS was a bad idea from the start, and this result merely validation of that belief; their priority is Yale and its brand, not the peers and students in Singapore who suddenly find themselves victims of the sort of unilateral decision-making normalised, and aped at all levels, in an authoritarian state.

Writing for The Octant, Yale-NUS alumni Daryl Yang accepts that what’s done can’t be undone, but argues for the protection of academic freedom, student activism, and progressive policies at the New College, with Yale-NUS and USP faculty and students being active participants in the conceptualisation and creation of this new institution.

What to fight for, and how to strategise for it, are matters that should be led by those most affected by these changes. But there are also aspects that concern Singaporeans as a whole, and that we can, and should, all be asking questions about.

If the Ministry of Education felt so strongly about the cancellation of a workshop for a small number of students, what about the end of the entire college?

Here’s one: what was the Ministry of Education’s role in all this? A lot of public funds went into Yale-NUS College, so the government isn't just some disinterested observer. Considering that there are accounts of MOE vetting hiring decisions at universities, it seems implausible that something as big as this would happen with the Ministry merely being “informed”. When Yale-NUS College shut down a week-long workshop, then-Minister for Education Ong Ye Kung ended up making a speech in Parliament in response to questions, in which he claimed that “political conscientisation is not the taxpayer’s idea of what education means” and launched an unwarranted attack on Alfian. If the ministry felt so strongly about the cancellation of a workshop for a small number of students, what about the end of the entire college? What does the current Minister for Education, Chan Chun Sing, think about all this? What role did MOE play, if any? And even if it didn’t play any role, what accountability is there to Singaporeans whose taxes have helped fund Yale-NUS for the past decade?

Regardless of whether one personally cares for Yale-NUS College or the University Scholars Programme, last Friday’s announcement was a worrying display of unilateral decision-making and arbitrary exercises of power. This sort of practice—devoid of consultation, oversight, or checks and balances—can affect anyone. It’s become a habit in Singapore, not just in NUS, but in multiple institutions, companies, organisations, and groups. It’s important that we resist this, and insist upon fair and considered due process, wherever we encounter it. There should be "no more top-down", not only in NUS, but everywhere that should have accountable and fair decision-making processes.

Ultimately, the spirit of student and youth activism in Singapore should be protected and fostered regardless of whether Yale-NUS College survives. Multiple cohorts worked hard to regain ground that was lost decades ago when student activism was clamped down on, alongside the civil liberties of all Singaporeans. This ground shouldn’t be lost again. Young activists aren’t threats to Singapore; they are citizens who are accessing their rights. The least we can do is stand in solidarity with them.

Questions sent

In writing this piece, I sent questions to Yale, NUS, Yale-NUS, and MOE. I’ve listed them below.

- To Yale:

- What deliberations were involved in coming to this decision? How many people were involved in making this decision?

- Was there any consultation within Yale about this decision?

- Did Yale push for consultation with the faculty, students, and other stakeholders in Yale-NUS before this decision was made? Why was there ultimately no consultation in Singapore?

- What will happen to faculty who transferred from Yale to Yale-NUS in Singapore? For instance, a Dean of Faculty just moved from Yale to Yale-NUS in January this year.

- How involved is Yale now in the transition?

- There has been speculation in Singapore that this sudden announcement has to do with political considerations, and that it is precisely because Yale-NUS is a successful liberal arts college with students who are politically engaged that there was pressure for it to be shut down. What is Yale's response to this speculation?

- To NUS and Yale-NUS:

- What deliberations were involved in coming to this decision? How many people were involved in making this decision? What was the process of coming to this decision?

- Why was there no consultation with Yale-NUS College's own president, Tan Tai Yong?

- Why was there no consultation with faculty and students, or, at the very least, more advance notice?

- Why was the announcement made after the new academic year had opened, and freshmen had paid their fees?

- What will NUS/Yale-NUS do if there are students, particularly freshmen, who might want to transfer out of Yale-NUS College or USP after this announcement?

- I understand that MOE was informed of this matter; what role did MOE play in this decision?

- There has been speculation that this decision is related to issues of academic freedom and also student organising and activism at Yale-NUS, and that there were political considerations going into this matter. What is NUS and Yale-NUS' response to such speculation?

- Was there any consideration of expanding Yale-NUS rather than merging or closing it, if the goal was to expand liberal arts education in Singapore?

- As of March 2021, the Yale-NUS Endowment Fund stands at S$429.8 million. What will happen to this money?

- To the Ministry of Education:

- I understand that the Singapore government is the main funder for Yale-NUS. How much is allocated by the Singapore government to the college every year?

- Will these funds now be redirected to New College?

- I understand from reporting in The Octant that Prof Tan Eng Chye raised the idea of ending the Yale-NUS partnership to MOE in July. What was MOE’s response to Prof Tan?

- What role, if any, did MOE play in the discussions between Yale and NUS? Did MOE have much sway in terms of decision-making power?

- Some students have said that the decision and announcement was unfair, particularly since first-year students have already paid their fees and begun the new academic year before finding out about the impending closure of Yale-NUS in 2025. What is MOE’s position or response to these students’ situation?

So far, I have received responses from Yale, Yale-NUS, and NUS, although none answered my questions directly. Yale pointed me to existing material already referenced and linked in this piece, as well as to a letter written by Pericles Lewis to the Yale-NUS community. Yale-NUS referred me to the FAQ page on New College, also already referenced in this piece. NUS said: "We have no further information to share concerning this announcement."

I’ll update this story, or do a follow-up, if/when I hear anything substantial from the others.

Thank you for making it through this whole piece! Again, if you'd like to support the students' #NoMoreTopDown petition, please sign it here and share it widely.

Also, feel free to forward or share this piece with anyone who might find it interesting or useful! If you're not yet a Milo Peng Funder and would like to become one, that's great! Or you can also opt to leave a tip via Ko-Fi.