By Tachibanaki Toshiaki for Nippon.com

Once, many Japanese believed in the ideal that all children deserved the same access to education. However, increasing numbers of parents seem to think it “natural” or “inevitable” that a family’s income dictate access to education. The right to quality higher education is also tending towards the hereditary, as national government offices are filled with University of Tokyo graduates whose own children move from famous prep schools on to that same university. An exploration of these issues and a search for a solution.

Inequality of Results and of Opportunity

We have reached a consensus that Japan’s society has become distinctly stratified. Income inequality is growing, and people seem to accept that society is divided between the wealthy and a large impoverished class.

We must understand that inequality manifests as more than income disparity, or what we term inequality of results, but also inequality of opportunity. So, when addressing inequality in general, we must not ignore opportunity distribution, such as the availability of education or disparities in hiring or promotion within businesses. Below, though, I focus on the issue of education disparity.

To properly understand the issue, it is best to start from the consensus belief that children’s access to educational opportunities should not differ based on parental income. Most people would agree that when a child who shows academic ability and motivation is unable to attend college due to lack of financial means, it is an example of inequality of opportunity. It is also commonly believed that inequality in educational opportunity is unacceptable.

Affordable Public Education Preserves Equality

Many countries set up scholarship or other relief systems precisely to allow children from low-income families to attend university. For example, even in the United States, which has a major problem with income inequality, there is a strong consensus that people should have access to a proper education as a jumping-off point in life, so its tuition assistance system is far more comprehensive than Japan’s. The prevailing idea there seems to be that once a person has received their education and entered working society, any income inequality comes as a result of individual work ethic and productivity, in consistency with economic principles.

Japan also has a traditional strong preference toward educational equality, though not to the level of the United States. Japan’s approach has tended away from scholarship systems in favor of keeping tuition fees for public schools low so that children from low-income families can attend high school and university more easily. This fact would seem to offer evidence that, as a society, Japan accepts equal access to educational opportunity as a worthwhile pursuit.

However, the actual trend in tuition seems to argue against that acceptance. 50 years ago, tuition for national public universities was around ¥12,000 per year, but that figure rose to ¥200,000 25 years ago, while now it is ¥530,000, putting university out of reach for low-income families. A better scholarship system would ease this issue, but Japan lags behind other developed nations in this area. This rise in tuition fees represents an actual barrier to equality of education opportunity, something that seems to be more and more commonly understood in Japan.

Rising Acceptance for Inequality of Educational Opportunity

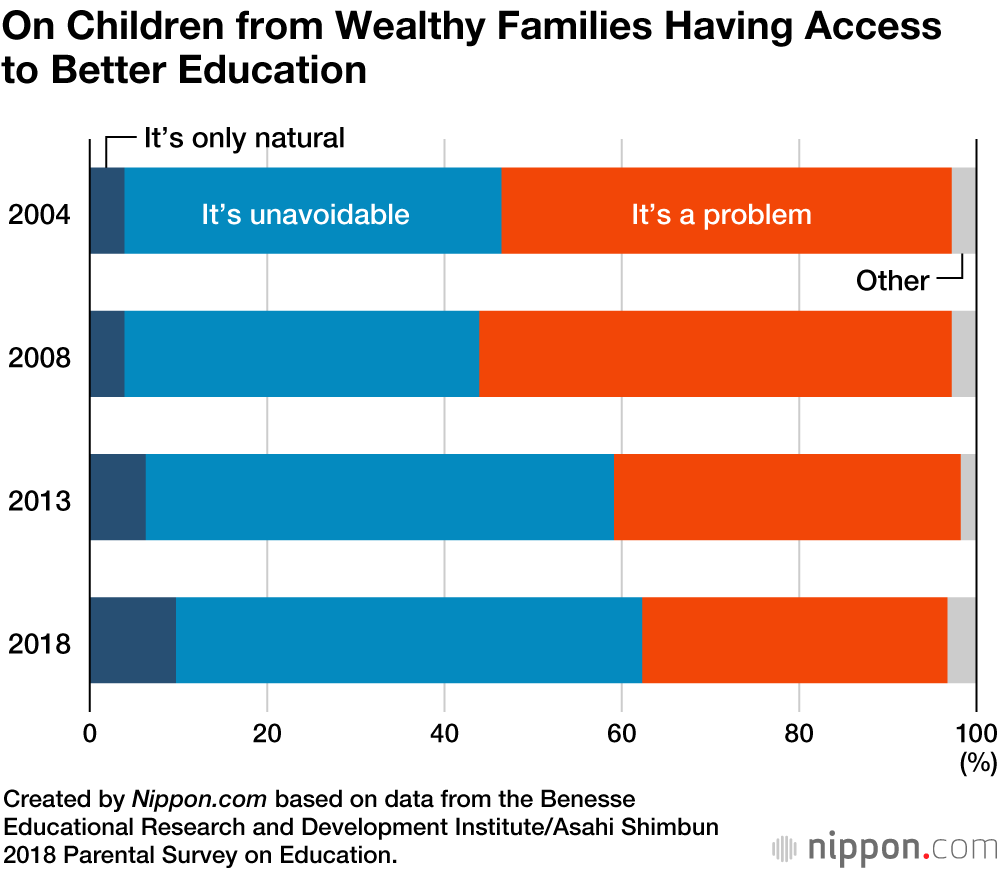

The chart below shows the views of parents or guardians on inequality in education. It charts the change in answers to the question “What do you think of the trend toward better educational opportunities for children of high-income families?”

In 2018, just two years ago, 9.7% of respondents thought it was “only natural” for wealthy children to have access to higher-quality education, while 52.6% said it was “unavoidable,” meaning a total of 62.3% seem to feel educational inequality is acceptable to some degree.

In 2004 that total was 46.4%. In just 14 years this increased by 15.9 percentage points, which reflects a significant change in the number of people who accept educational inequality. The chart does not show what demographic accepts that inequality, but in general it seems that many are in higher-income families living in large cities and university graduates themselves. Those who answered, “it’s a problem,” on the other hand, include many living in smaller cities or rural areas who have no university education and lower incomes.

Higher Education Becoming Hereditary

Most people in Japan once held to the idea that educational opportunities should be open to all because higher education could lead to better employment after graduation. That would then lead to higher income potential and thus a benefit to the economy as a whole. Why have people stopped believing in this kind of equal opportunity?

I think there are several possible explanations. First, Japanese parents are becoming less interested in the education of other peoples’ children, though I would not go so far as to say they only care about their own children. The fact that more children having access to higher education correlates to better national productivity, and thus a stronger national economy, seems to be met with indifference.

Second, successful parents who themselves have higher educational backgrounds and higher incomes desire the same for their own children, and eventually view the right to education as hereditary.

Third, there are more and more who believe that offering educational opportunities to children with lesser abilities or lower motivation, no matter how good the education, could be a waste of school resources.

Fourth, it is likely that many parents living in poverty are so focused on working that they have no emotional or mental reserves to think about their children’s education. And without the money to send their children to cram schools, their children struggle to achieve high academic performance.

These four reasons together have contributed to a majority of parents in Japan feeling that inequality in educational opportunity, or educational disparity itself, is inevitable. The concrete result of this phenomenon is that we are now in an age where children of high-income families simply receive better education than those in low-income families. More symbolically, this is reflected in the tendency of children attending the University of Tokyo, a public university, to come from very high-income families. Not so long ago, it was commonly accepted that children of poor families had a place at the nation’s public universities, but those days are over.

Toward an End to Cram Schools

In truth, one specific reason for this educational inequality is Japan and east Asia’s unique cram school culture. The children who go to cram schools tend to live in large cities and come from middle- or high-income families. The extra assistance cram schools offer results in higher performance on entrance exams, and thus access to better higher education. Since poor families cannot afford to send their children to cram school, their school performance suffers in comparison. I go into more detail on this issue in my book Kyōiku kakusa no keizaigaku (The Economics of Educational Inequality).

The Japanese style of cram school does not exist in the West, and in fact the very concept is often seen by Western observers as an effort to make up for inadequacies in Japan’s public educational institutions. The most effective way to improve Japan’s educational quality without being having to depend on cram schools would be to decrease public school class sizes and to improve the quality of teachers. This will require a massive investment in public education, of course, but the fact is that the ratio of Japan’s educational investment to GDP is currently much lower than most developed nations. Above all, the first step is for Japan to increase public education spending so that Japan’s children can once again have equal access to educational opportunities.

Originally published in Japanese.

Tachibanaki Toshiaki

Born in 1943 in Hyōgo Prefecture. Earned his PhD from Johns Hopkins University. Worked in research and education at institutions in France, the United States, Britain, and Germany, before becoming a professor of economics at Kyoto University; also taught at Dōshisha University and Kyoto Women’s University. Former president of the Japanese Economic Association. Publications include Kakusa shakai (Social Polarization), Jojo kakusa (Gaps Among Women), and Shiawase no keizaigaku (Economics of Happiness). Author and editor of over 100 books in Japanese and English.